Like any good psychology student, I remember initially learning about cognitive dissonance, and thought I understood it pretty well. In general, the theory proposes that when an individual has "belief dilemmas" where that person encounters conflict with new information, there's an effort to restore balance to beliefs by changing something within their cognition. Using a direct example from battering intervention work, if I want to control a situation and make my partner do something she does not want to do, and when I do so she becomes upset - and I notice and care about her response - then I will need to change something in my beliefs about controlling her in order to balance my desired result (that I get what I want and my partner goes along with that desire).

The theory is that part of the disconnect with people who choose abusive and violent behavior has to do with not noticing impacts, or caring about their partner's response. So within battering intervention work, we make a lot of effort to raise awareness of impacts on self and others, as well as try to get individuals to be more introspective and self-aware of how chosen behavior is abusive or violent.

But what if it's not that simple, and all these years that I've believed we just need to increase cognitive dissonance aren't exactly striking the chord of changing beliefs and behavior?

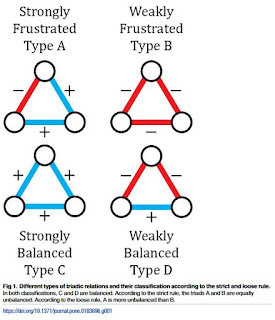

As far back as 1958, Fritz Heider proposed "Balance Theory (p. 90 of Milburn's book)" which hypothesizes that triads of relationships that have a positive or negative attribute (valance). He proposed that balance in belief systems needs an odd number of positive relationships (either one or three) to be balanced.

So using current events to illustrate, with the recent Twitter post by President Trump sparking debate about his directly racist statement, if someone supports Trump, but dislikes racism, then to create balance that person would need to either begin to disagree with or dislike Trump, or agree with or begin to like racism.

The problem is that while I learned about cognitive dissonance and balance theory enough to remember them easily, I did not remember the limitations and problems with these theories.

One limitation, and it's a big one, is that when fear or hatred is involved (very strong negative attitudes), individual's cognitions may persist as imbalanced. I cannot count the number of times I have worked with individuals in BIP who hate their ex-partner with such passion that they are unable and unwilling to consider how the damage they cause in that relationships directly damages relationships with their own children with their ex-partner. That hatred is so strong there is no motivation to consider personal choices that are abusive or violent, but rather there is a highly targeted focus on that ex-partner's behavior and why it is wrong.

This means that within intervention work, we need to more strongly consider methods of confronting hatred. Trying to convince someone to have empathy toward a person they hate is most likely going to be unsuccessful because the imbalance in cognition is going to be accepted. No matter the potential harm to themselves and others, an individual entrenched in their hatred will most likely be unable to shift their behavior toward respect and health.

A second limitation has to do with situations wherein an individual holds two strongly held beliefs that contradict each other. The text suggests that researchers were at a loss to account for this inconsistency in beliefs, but offers some suggestions on how people resolve belief dilemmas that may offer insight into how someone can maintain two strongly held beliefs that contradict.

Resolution of Belief Dilemmas:

- DENIAL: This is the simplest way to eliminate inconsistencies in belief systems, and anyone who works within intervention understands this. You can enter into denial by changing the way one of the objects is valued, or by denying the relationship between the two objects of denial. Fortunately, this is also the weakest method of resolving belief dilemmas, and denial will break down if there are too many inconsistencies, or if there is too much conflicting evidence of other possible beliefs. In general, BIP does a decent job of confronting denial through both methods - introducing and reflecting on inconsistent beliefs, and by offering evidence of the impacts of abusive and violent behavior.

- BOLSTERING: When someone adds additional elements to an inconsistent pair of beliefs that serve to overpower another belief system, they bolster one side of the belief dilemma in such a way that the dilemma ends. This is a common challenge in BIP classes, and it is mostly framed as "collusion." When group participants support entitled belief systems, they often do so to bolster their individual sense of being right, and diminish the sense that their partner's perspective matters. Again, in general, BIP is decent at addressing bolstering behavior, and working to get class participants to hold each other to a higher standard - to discuss respectful and healthy beliefs, and bolster the side of the belief dilemma that supports changing behavior. It can be useful to be more cognizant of this process, and why individuals use it to continue hurtful behavior, and also to understand how a focus on discussing respectful and healthy alternatives serves to bolster in a positive way.

- DIFFERENTIATION: A divide and conquer technique, this resolution involves separating two belief systems into a pair that is consistent, and a pair that is inconsistent - therefore creating an illusion of balance. There are methods used in BIP to exploit differentiation, and I am not sure I fully agree with the technique, but the ManAlive approach is probably the easiest to describe. As a part of their curriculum, they have individuals in classes identify their "Hit Man" which consists of all the abusive, violent, entitled, and hurtful belief systems. Individuals in the class then compare that to healthy, respectful, and supportive belief systems in an attempt to diminish harm. I am concerned that this can potentially create that illusion of balance rather than actually creating balance by changing beliefs - but I am also willing to recognize that if someone is able to diminish hurtful belief systems through this analysis then that's important work.

- TRANSCENDENCE: Methods of analyzing belief systems sometimes involve creating reasoning for the beliefs themselves. This in essence is transcendence of the inconsistencies themselves. The example Milburn uses invokes religious perspectives of God, and a dilemma that if God is perceived as pure good, how can God allow evil to exist? To transcend this dilemma, individuals explain this by considering the concept of "free will" and how it's not God allowing evil, but rather individual people choosing the path of evil. By coming up with this reason, it dissolves the dilemma. Consider how frequently individual participants in BIP want to come up with reasons for their behavior, and how often it focuses on a reason that blames others. In BIP, the methods of using transcendence could involve discussing entitlement and how believing you are better than others, believing others are less than you, and believing you deserve something from others allows individuals to be abusive and violent. If that is the reason for hurting others, then it is reasonable to address entitlement and begin to dismantle it to instead create support and care for a partner and for children.

Further discussion points out that attitudes that are important to an individual are more stable than those that are less important. So in essence, instilling a sense of importance to be respectful and healthy could go a long way toward motivating change in people who choose abusive behavior. The challenge is that often a sense of righteousness is much more important to entitled individuals than health and respect. This means that BIP facilitators need to be mindful of topics that participants are less knowledgeable of. Often this is in topics of respect and health, and while it is important to focus on and discuss abusive and violent behavior, individuals who have been abusive or violent often believe their innocence is the most important attitude, and will find several ways to prove that innocence and ignore identifying how they have been abusive or violent. If we can bolster health and respect, it is more likely that individuals who are closely tied to their belief of innocence will relax those beliefs enough to find methods of change. Researcher Jon Krosnick suggests that when there are two attitudes of equal importance, the above belief resolutions become possible, but in general people will only change their less important beliefs.

When considering how much we focus on belief change in BIP, we need to be much more aware of how this happens. Ableson suggested in his work on cognitive dissonance that beliefs are like possessions - that people hold on to them, value them, and are often reluctant to let them go. It's possible to directly influence changes in beliefs the more we can shift how people view what's important, and how they can connect with alternate perspectives. Entitlement is often very strong for people who choose abuse and violence, and as a result, this entitlement is also of high importance to them. It's possible to create a stronger importance in respect and health, and how we navigate those discussions can make all the difference.